This is another weekend cross-post from my First World War blog — a realtime account of your modern world being born in blood and fire a century ago. Today’s installment is about the effects the Great War was already having on Americans two years before the United States entered the war — and what Americans have always valued in their news media.

27 February 1915 – Test Case

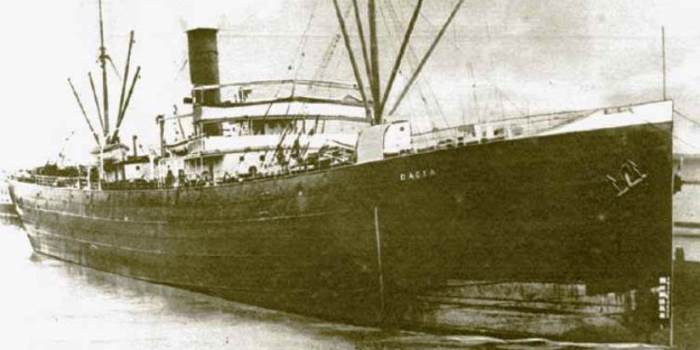

The French auxiliary cruiser Europe is patrolling the southwestern approaches to the English Channel this afternoon when she sights the SS Dacia, the very steamer that she has sailed out to intercept. Carrying a cargo of cotton from Galveston, Texas to neutral Rotterdam, but consigned to the German industrial port of Bremen, the Dacia has already been a subject of controversy for weeks when she is ordered to stop. As she arrives in the port of Brest tomorrow still flying the American flag, the Dacia is destined to become an important legal test case in the allied blockade of Germany.

The new owner of the Dacia is Edward Breitung Jr., son of a successful Michigan mining speculator who wants to expand his family business into international shipping. Seeking a suitable ship in December, one of his agents discovered the Dacia interned in Port Arthur. The Hamburg-American line had been trying to sell off its expensive, idle assets at fire-sale prices rather than risk sailing them into the teeth of the blockade. Germany began the war with the world’s second largest merchant fleet, but most of those ships now sit at anchor in neutral ports just like the Dacia. The allies worry that Breitung will set a precedent for Germany to regain its maritime trade by selling these idle vessels to private parties, who can then re-flag them and circumvent the blockade.

News of the Dacia‘s sale hit the British press almost as soon as Breitung closed the deal for the ship on January 15th. The conservative Times opined that “If she sails, she must be stopped, and the novel point of international law which she threatens to raise must be brought to a definite decision.” With only one notable exception, the Daily News, liberal papers also worry that Germany’s war effort will be revived unless the boat is prevented from reaching her destination. In fact, President Wilson has a bill before Congress to purchase even more interned German vessels, enlarging America’s woefully-small merchant fleet but also adding further heat to the diplomatic exchanges between London and Washington regarding the blockade.

After the Dacia set sail on the last day of January, the British Foreign Office — which actually runs the blockade operation — decided to let France intercept her, preventing further deterioration in Anglo-American relations by putting the whole question into a French prize court. Watching intently from the southeastern United States are four million Americans employed by a devastated cotton industry, which has seen the price of its product cut in half by wartime market disruptions from which it is only now beginning to recover.

The French Prize Council does not even recognize transfers of belligerent vessels in wartime. Breitung nevertheless submits reams of documentation to the court, which renders their decision in August. While recognizing that Breitung’s purchase of the vessel was made in good faith, the court decides that the sale contract — in which the Hamburg-America line stipulated that Breitung must re-flag the Dacia in the United States — is proof of an effort to circumvent the blockade, and declares the seizure valid.

The Dacia is then re-flagged again as a French cargo ship, the SS Yser, and refit as a cable ship. But she does not serve long in this new capacity. In November, she is stopped by the U-38, a submarine commanded by the famous Captain Max Valentiner, on her way from Cardiff to Tunisia. After allowing the crew to take to their boats, Valentiner’s men — who are enforcing Germany’s own counter-blockade against the allies — scuttle the Yser with explosive charges.

Under pressure from the State Department, the Senate eventually tables their bill to purchase German ships sitting idle in American harbors. Cotton sees a rebound in prices, but a full recovery appears to be impossible while the war rages and the blockades continue.

Nor is the Dacia Breitung’s only interaction with courts this year. On April 24th, Breitung is forced to testify in a lawsuit after his son-in-law Max Kleist charges him with alienating the affections of his daughter Juliet. In his defense, the millionaire claims that his daughter was unhappy with the elopement, and asked him to secure an annulment. The trial is closely covered by newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune:

Breitung became nervous in the witness chair, rolled his handkerchief into a ball, dabbed his moist face, and gave other signs of mental disturbace as he admitted, under heavy fire, that he had from the beginning talked about annulling the marriage and about sending Kleist far away.

Admitting that he hired detectives to follow Kleist, and that his wife had to restrain him from assaulting his daughter’s husband when he called her a “dirty girl,” Breitung’s sensational family turmoil quickly overtakes matters of international law and debates about various articles of the 1909 London Naval Conference — at least as far as American journalists are concerned. The distraction, and the shrewd decision to land the matter in France rather than England, will bury the outcome of Breitung’s test case under a pile of sleazy headlines. Some things never change.