This is another cross-post from the Great War Blog, a daily diary of your modern world being born in blood and fire a century ago. Today’s installment is about a Supreme Court decision that ought to have been a watershed civil rights moment, but became a lost opportunity for a nation still haunted by its Civil War a half-century before.

21 June 1915 – Grandfather Clause

Far from the battlefields of a world at war, America is a nation cleft by unresolved social divisions remaining from the nation’s self-immolation a half-century ago; ours was a deeply racist, and deeply flawed, society in 1915, with another war at the heart of our national trauma. Whereas the trenches and primitive automatic fire of 1871 still haunted France in 1914, affecting her Army’s doctrine and performance even a year later, in 1917 the American nation will send an Army to war seeking extirpation of national ghosts that were created by the trenches and primitive automatic fire of Grant’s final campaign on Virginia in 1865.

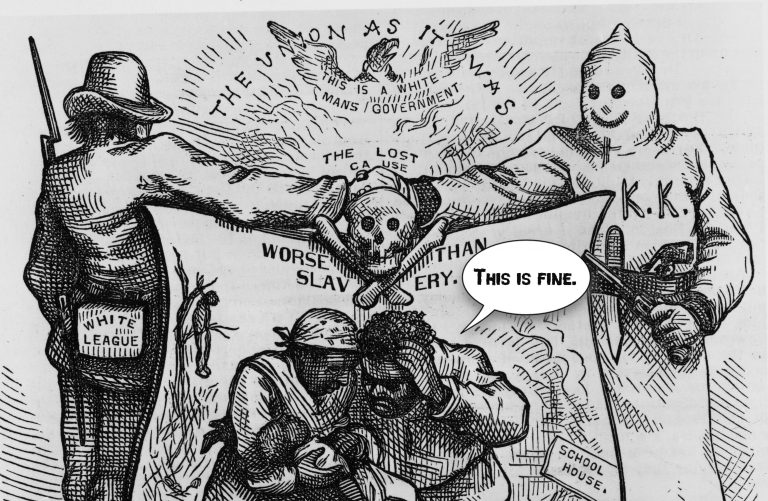

Today, a unanimous United States Supreme Court issues its decision in Guinn v United States finding that the ‘grandfather clause’ in Oklahoma’s voting eligibility law blatantly violates the letter and spirit of the Fifteenth Amendment. Writing the court’s opinion, Chief Justice Edward White (see above photo, at center) seems an unlikely character to make such legal writ: too young to serve when the Civil War began, he was a still-young Confederate officer when it ended; a Louisianan, White is a past member of the infamous White League who is undoubtedly all too familiar with the despicable habits of Southern disenfrachisement. Yet his opinion is a clear, full-throated confirmation of the constitutional liberty of freedmen:

(T)here seems no escape from the conclusion that to hold that there was even possibility for dispute on the subject would be but to declare that the Fifteenth Amendment not only had not the self-executing power which it has been recognized to have from the beginning, but that its provisions were wholly inoperative, because susceptible of being rendered inapplicable by mere forms of expression embodying no exercise of judgment and resting upon no discernible reason other than the purpose to disregard the prohibitions of the Amendment by creating a standard of voting which on its face was, in substance, but a revitalization of conditions which, when they prevailed in the past, had been destroyed by the self-operative force of the Amendment.

Oklahoma did not have a ‘grandfather clause’ in its constitution when it was admitted as a state in 1907. The change was among the first orders of business when the legislature met, however, for Oklahoma has become a destination of sorts for the now-emerging flight of black labor out of the Old South in what will become known as the Great Migration. In particular, a large cluster of Negro citizens around the Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood is becoming known as the Black Wall Street for the area’s economic prosperity and nationwide cultural impact. Seeking to preserve and enshrine white electoral supremacy under such a challenge, the legislature ignored the Fifteenth Amendment and denied the ballot to anyone whose grandfather was ineligible to vote in 1866.

(N)o person shall be registered . . . or allowed to vote, unless he be able to read and write any section of the [state] constitution . . . no person who was, on January 1, 1866, or at any time prior thereto, under any form of government, or who at that time resided in some foreign nation, and no lineal descendant of such person shall be denied the right to vote because of his inability to read and write sections [of the state constitution.]

During the election of 1910, racial disenfranchisement was so blatant and pervasive that a pair of US attorneys felt morally obligated to charge two election officers, Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal, with violating federal election laws. Convicted against the odds by an all-white jury in 1911, the stunned men have appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which now upholds their sentences. The states with similar laws on the books, including Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia, all see them struck down by this decision.

Yet the Guinn ruling is too narrow in scope, leaving aside the question of literacy tests and acknowledging no overarching constitutional right to the franchise. Meeting in 1916, Oklahoma’s legislature passes another measure to deny the ballot to anyone who did not vote in 1914 or who does not register during a special 12-day period that year. This new law will also face a challenge, but the plea will not be heard in the Supreme Court until 1939. Quite simply, the court is too judicious in its application, and cannot keep pace with the creative efforts of Jim Crow-era legislatures to invent manifold new ways of disenfranchising black people.

It does not help matters that American racism is becoming even more entrenched and pronounced under the Wilson Administration, or that the president is deeply racist himself. During the first session of Congress held after his election, southern Democrats introduced no less than twenty racist bills to mandate segregated taxis and public transportation within the District of Columbia, to segregate federal employees, to exclude Negroes from serving as officers in the United States military, to prohibit interracial marriage, and to shut America’s doors to immigrants of African descent. Responding to these efforts with zeal, Wilson has issued executive orders to segregate the federal government in the District and the civil service across the nation, imposing segregation on the Navy Department and replacing all blacks with whites. These measures have a negative effect on American readiness, making them stand out in sharp contrast to Wilson’s preparedness efforts.

On the one hand, this is an extraordinarily fertile moment in the history of American blackness. A new organization called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP, is rejecting the collaborationist approach of Booker T. Washington for a more militant agenda which demands full citizenship for black Americans. Opposing the system of white supremacy is not easy; it will take decades yet to achieve nominal political equality and a “right to vote.” Indeed, the fight is still not over in our time a century later, but the trend is already visible in 1915.

On the other hand, the Great War is polarizing societies and fracturing political systems everywhere, not just the United States. While the country is at the beginning of a huge wave of anti-German sentiment, the sight of black Americans in military uniform proves too much for some white citizens, sparking riots. The rising success of black communities like the one in Greenwood, Oklahoma tends to exacerbate racial tensions rather than relieve them, for within the “separate but equal” framework of Jim Crow, any semblance of actual economic equality frightens white people too much for them to permit it. The new age of mass violence is accompanied by episodes of communal violence, and America is no exception. Despite today’s ruling — or perhaps in part because of it — in 1921, Tulsa will see the bloodiest riot in the nation’s history when the ‘Black Wall Street’ is burned to the ground by an angry white mob.